Now that I’ve finished Steven Pinker’s momentous 2002 book, The Blank Slate, I find it somewhat hard to write about. It’s not that I didn’t have a strong reaction. I did: I loved it. It’s that there’s so much: The Blank Slate is an exhaustive, many-avenued, in-depth, provocative work – friendly and caustic all at once – such a dense, rich mixture of such variety and depth that it’s almost hard to know what I think of it after one reading. There are small chapters – even halves of chapters – that could set me thinking for months. For example, one of my favorite recent books, Thomas Sowell’s A Conflict of Visions, comes up partway through one chapter, is given the most virtuosic analysis imaginable, and then stowed away, just one single prong in an extensive, many-layered argument that Pinker’s making in just one small quadrant of this tour-de-force. It’s a massive work, a memorable one, but a hard one to come away from with a coherent take.

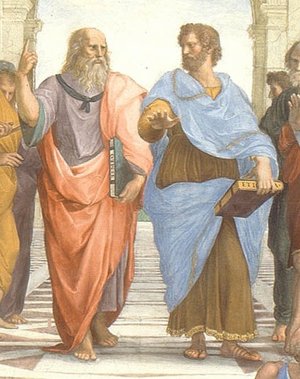

Pinker’s main theory is that there are three pervasive cultural myths that we employ to deny the possibility of an innate human nature: the notion that humans are born as Lockean blank slates (with no innate capacities or predilections), the conception of humans as Rousseauian noble savages (innately gentle, peaceful, and only corrupted by social constructionism and civilization), and the belief in a Cartesian “ghost in the machine” – the belief that we possess a mind or a soul that is phantasmic in substance rather than biological, unbound by the dictates of regular physiology (and nature).

Continue reading “The Blank Slate”