Picture this: a powerful white man walks into a room full of African American parents. He tells them that he, the head of schools in a major American city, is going to close their neighborhood school. The parents get angry. They yell at him. One woman calls him a racist.

Calmly, the man asks her what grade her child is in.

“Third.”

Okay, there are 70 third graders at this school, he says. “Do you know how many third graders are reading where they’re supposed to be?”

The woman confesses that she doesn’t know.

“Six.”

That’s when he turns to the audience.

“Do any of you know if your kids can read at grade level?”

Let’s pause here and just admire the man’s arrogance. Imagine if some educational bigshot came strolling into your town, put his finger on your chest, and asked, “You, there! Do you really know if your child can read?”

“Well,” you might stammer, “I think so . . . “

“But do you know if she can read . . . at grade level? Is she . . . proficient? Hmm?”

Well, for about seven years, not long ago, that basically happened all across America. This self-appointed guru came sauntering in and informed you that you were too stupid even to know how your own children were doing. Well, he’d give you a hint: they’re also pretty stupid.

Soon he stopped picking on just poor black mothers and went after white mothers in the suburbs. At one point he complained:

“It’s fascinating to me that some of the pushback is coming from . . . white suburban moms who — all of a sudden — their child isn’t as brilliant as they thought they were and their school isn’t quite as good as they thought they were . . .”

Starting to ring a bell?

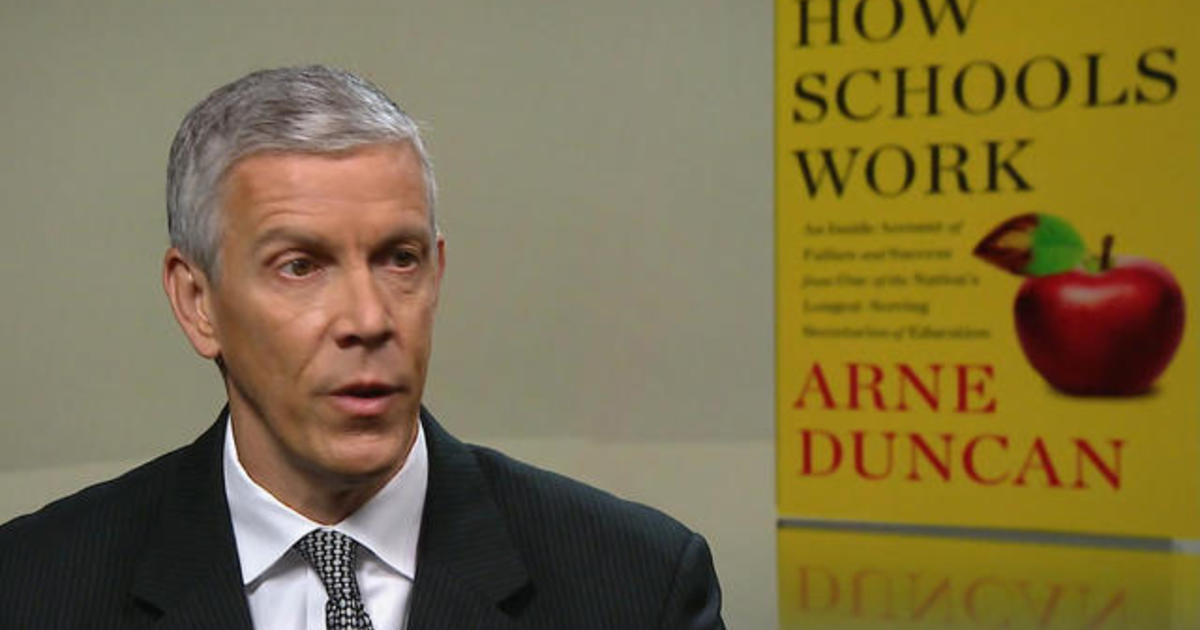

That’s right: that man I am talking about is Arne Duncan — who served as Barack Obama’s powerful Secretary of Education, has written a new book, and is still just as arrogant as ever.

***

That moment back in Chicago is a pivotal one in Duncan’s new book, How Schools Work. The young Duncan, a wunderkind, has just been handed the reins of the entire Chicago school system and, faced with his first taste of opposition in the form of those angry parents, somehow wins them over with his truth-telling, and as he puts it, “learns to always run into the fire.”

Later on, when he tries this arrogant-guy shtick with the entire country, it doesn’t go as well. Huge swathes of the American public basically tell Arne to go f-himself, thank you very much. We know how well our kids can read, bro.

But that night in Chicago? His shtick sort of works. He plays the classic Great White Hope card. These poor, black mothers lack political power. They live in a neighborhood that no one at City Halls gives a Rahm Emanuel about. Now here comes the brash new white guy, the downtown suit, playing truth-teller, peddling Real Data, the kind that the bosses usually keep hidden, and he is shuttering the school because he cares. Those mothers stop yelling and they listen — mostly because they have no other choice.

But that in itself isn’t weird. Urban reformers and politicians play the Great White Hope card all the time. Donald Trump, in his fashion, made this about as naked and even parodic as possible when he asked African American voters, “What do you have to lose?” This has been happening for a long time.

But what’s weird about Duncan is that he doesn’t just think he knows best. He thinks the schools have been LYING.

That school he shut down? Just before he pulls the plug, he goes on a little fact finding mission. He stops by to take in an awards night, and, sitting in the back with a great big frown on his face, draws an all-time oddball conclusion:

“I’d attended an event . . . celebrating the school’s achievement in science. The problem was that while some students did deserve the accolades, the school itself remained miserable.”

Can you believe those lousy school teachers? Celebrating mediocrity! They should have held a big “Why We Suck at Science” party. They could have shown the kids their dismal test scores. Arne walks out in a huff, certain this event is evidence of a conspiracy:

“[The schools] had not presented the data to the parents. Instead, they tried to craft a counter-narrative that the school was not as bad as it actually was . . .”

What a seriously odd thing to say. But Arne says it over and over in the book — and, a quick glance through the archives confirms — all through his tenure as Bigshot Teacher Boss.

Schools are lying to parents.

***

But let’s break this down a bit. Duncan is operating in a strange alternative universe in which he makes two odd assumptions:

1) Poor, minority parents in crime-ridden, under-resourced neighborhoods have NO inkling that their children aren’t exactly getting a fair shake at a great education.

2) If we just showed them the REAL DATA, they’d be horrified and would demand better for their kids.

This is such an odd misreading of reality.

First of all, let’s look at the first assumption: Parents have NO CLUE. This is wacky.

Let me venture a guess. Duncan indicates that these parents are poor, African American, and live in a neighborhood without a lot going for it. My guess is that these parents know their kids aren’t exactly attending the world’s best schools. My guess is that they know their neighborhoods are neglected, and that nobody at City Hall cares. They probably — if their schools are anything like the public schools on the wrong side of the tracks in Washington, D.C. — have noticed that their kids’ schools are old, crumbling, and lacking the basics, like textbooks from the current century — especially compared to the white schools across town, which basically look like mini U-Chicago campuses. It was like this in Washington, plain enough to see for anyone with a car. That’s why these parents are mad at ol’ Arne for wanting to close their school rather than throw it more resources in the first place.

I met these parents when I worked briefly at a Washington, D.C. charter school. There was one young man, bright, personable, engaged in school — whose writing level, I realized early on, was at least three or four years behind his peers’. His parents, at our conference, told me they knew that his neighborhood school had failed him. They described all the usuals — the fights in the halls, the lack of new books, the teachers — I remember this is the phrase they used — who had “retired in place.” They knew.

Then we get to the second assumption: That if they just had some DATA, a light would go off, they’d demand better, and schools would improve.

This is so amazingly, off-the-charts naive — it’s the kind of thing I’d expect a college sophomore to blurt out after learning that, OMG, wealth inequality exists in the United States. If only they had the correct data, they’d rise up!

Duncan seems to believe this is the case with the schools.

There are so many things to question here:

–People will only act if they see the data? (Have you met “people” before? They act for lots and lots of reasons, but sadly “objective data” is not usually in the top 10.)

–Are we sure that standardized test data is really what any parent wants to act on?

–Are we sure that standardized test data is an accurate measure of . . . anything?

–So historically marginalized and ignored people, all-too-aware of their own powerlessness — victims of discrimination their whole lives, from a system so wide and deep they can barely get their minds around it — are suddenly going to not only demand change in their schools, but somehow win the kind of money and resources needed to make a difference in neighborhoods no one in the broader city cares about?

But Arne expects us to believe that when he takes some of these parents a few blocks away to some of the white schools (Question: Did they ride in his car?) they are shocked — positively shocked! — that white kids are getting a way better education. Imagine that! Gambling happening . . . at Rick’s Cafe in Casablanca!

You’re SUCH a truth-teller, Arne! Whatever would we have done without you?

***

But I wouldn’t be writing about this if Arne Duncan were just some random, arrogant superintendent out in West Whogivesashit Kentucky. No. Arne Duncan was the most consequential Ed Secretary of the last fifty years. He was a man very much in step with his times, and a man whose approach had a huge impact on a generation of students, teachers, and schools. His arrogance, I’m afraid, is the arrogance of a whole generation of educational reformers, which is still very much in power.

What’s dangerous about them is that not only do they think they know better — despite not ever having taught in a classroom — but that they have the “data” to prove it. I say “data” in quotes because the standardized tests that Duncan has always rested his case on — going back to that night at the school in Chicago — has always been proven flimsy and questionable by the real scientists, guys like Daniel Koretz, professor at Harvard and the author of The Testing Charade, who once sat in a room and told Duncan and his minions why they were wrong. But Duncan didn’t listen. In order for him to be the Great Truth Teller, the Bringer of Data, he had to buy all-in on the notion of standardized tests that would give him that data. When a scientist like Koretz warned him that an overreliance on a test would cause teachers to start doing test prep, not education, Duncan didn’t listen. When Koretz warned him that teachers might even start cheating to save their jobs and their reputations, Duncan didn’t listen. When Koretz warned him that the data itself was deeply unreliable, Duncan didn’t listen.

Are you surprised?

His was the arrogance of so many ed reformers: Only OUR tools, our metrics, our standardized tests can tell you what’s really going on. Without those, nobody ever would have known, including their parents, that poor and minority children aren’t getting a fair shake at their schools.

Here’s the delicious irony in the whole thing. It was only when reformers like Arne Duncan started tying teacher evaluations to standardized test scores that American schools actually started lying about what they were doing.

Arne made the system worse. Before that, schools weren’t “lying” about their performance. Please. Poor urban schools like the ones that Duncan castigates and closes down were doing the best that they can with the limited resources and seemingly unlimited societal problems being shoved in their doors every morning. They are doing the best they can to be beacons of light and hope in the middle of incredible and staggering want. They know they aren’t Beverly Hills High. They know their students aren’t exactly reading Charles Dickens. But they also know that these kids too need to be celebrated. They know that for these kids — and for their teachers — you have to walk into school every morning suspending your disbelief about the pretty apparent reality around you. You HAVE to believe that every kid can learn. You have to celebrate these kids. That’s what Duncan is really seeing when he attends that science awards night. But Arne Duncan doesn’t get what’s going on — because he never taught in schools in the first place. He sees these schools in the stark, black-and-white terms of an outsider. Clearly they must be lying.

Good thing we had Arne Duncan around to show us what was really going on.

***

Now there is a point in all of this. Duncan, I can tell, is writing this book in a way to show critics of his policies like me that his heart was in the right place. This is true. These schools are lying, in a way, but not for the reason Duncan claims. In fact, it’s not even a lie at all. It’s permission. We are giving permission for too many minority students to attend schools that definitely aren’t up to par. But we also permit them to live in crime-ridden neighborhoods, policed by departments that they don’t trust. These neighborhoods were often created by racist policies that herded African Americans into modern ghettos with no hope of rising to the middle class. We permitted all of this — and it’s much vaster than the tiny little example of it in some elementary school in Chicago that Arne Duncan, do-gooder, stumbles onto six months into his term as schools CEO.

It’s way, way bigger, my friend.

Look a little harder.