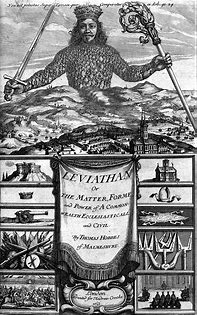

Thomas Hobbes’s famous work of political philosophy, Leviathan, was another tome that I’d inexplicably kept on my shelf in the twenty or so years since I first “read” it in college. Why? I’m not sure. It is a tome – a 500-page book taking up some two inches of width in my bookshelves all these years. Once I’d read Locke, I knew I had to read Hobbes. It kept coming up all over the place, in both the primary and secondary literature I’ve been reading. I knew the basics – that it was written before the Enlightenment, all the way back in 1651, that it was a singular, singular book, and I knew all about the “nasty, brutish, and short” life that Hobbes theorized for men in the state of nature.

I had expected it to be bracing – a kind of apocalyptic vision of humanity, cleansing, a jolt, a condensed dose of something powerful. Given my fascination with a – if not dim, at least realistic, capacious – view of human nature, I imagined this would be a book I’d really appreciate, or at least find memorable.

It is – sort of.

Continue reading “Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan: The Philosophy to “Get Through””