I want to touch a little more on what Francis Fukuyama — in his new book, Liberalism and Its Discontents, sees as the main challenges to liberalism from the right and from the left. In both cases, he sees that liberalism’s central virtue – it’s protection of individual autonomy from the coercion of the stage – has been carried to extremes.

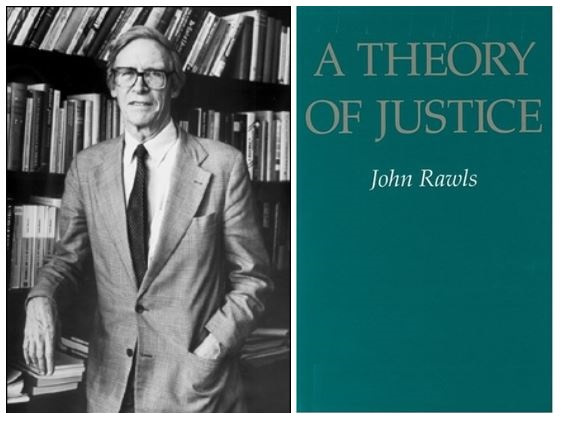

The challenges from the left are more obscure and harder to understand, likely because they are less materialistic and more idealistic and philosophical. In chapter 4, “The Sovereign Self,” Fukuyama makes the argument that autonomy has been taken too far by the political left to the point that we’re essentially all self-interested people, worshiping at the altar of our Rousseau-ian inner “selves,” which Fukuyama argues turns us away from the public-mindedness that we need to have to run a democratic republic. I found this point ultimately obscure and unconvincing, but I did find his history of this progress – from Martin Luther to Rousseau, to Immanuel Kant, to John Rawls – to be fascinating. It reminded me of Allan Bloom’s The Closing of the American Mind – an interesting account of our turn from civic-mindedness to self-involvement and even relativism. John Rawls, in particular, comes in for hard treatment from Fukuyama (as he did in Bloom’s book). I have never read Rawls and had thought of him as perhaps being the touchstone of the progressive left – the philosopher of redistribution. But for Fukuyama, he’s more than that – he’s the philosopher of non-judgmentalism, of value-free society, and above all, of relativism. This was a surprise to me, but, after all, I’ve never read Rawls, so what do I know?

But Fukuyama also makes a surprising argument here. He claims that few modern theorists really pay heed to the Hobbesian-Lockean-Jeffersonian tradition of natural rights – which was largely ontological (it was based on a theory of human nature, and on a hierarchy of human ends). Instead, Rawls’s view is today the dominant one – and it is deontological (not based on a theory of human nature or human ends or goods), but instead reflects a belief that the most sacred and important seat of the social contract is the fact that we are beings capable of moral choice. It doesn’t matter so much what choices we make (there’s the relativism), but only that we are free to choose. Fukuyama calls Rawls’s position “an unsustainable extreme” (54) and compares the shift from the Hobbesian tradition to Rawls to the shift from liberalism to neoliberalism. Later he writes that the Lockean tradition “enjoined tolerance for different conceptions of the good,” while Rawls “enjoins non-judgmentalism regarding other people’s life choices” (57).

I found this point very curious – tremendously interesting, and surely profound – but hard to understand, because Fukuyama doesn’t really flesh out the difference (and I don’t know enough about either Locke or Rawls to make sense of it). What does Fukuyama mean?

From what I understand about the Anglo-American tradition that Fukuyama cites, these thinkers (Hobbes, Locke, et al) believe that human beings possess certain innate characteristics – an innate nature, if you will – that led them to pursue certain ends: the avoidance of a violent death (in Hobbes), the desire for sociability, the desire to have an impartial state that can arbitrate disputes which will inherently arise due to human nature, the desire to secure “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” All of these are human ends in some sense, and suggest that only by cosigning the social contract with other similar humans can we attain these hoped-for ends. Rawls, on the other hand (and here I am groping based on what little I know about him), presupposed that humans would enter into society – instead he focused less on understanding the motives for that rather than on what conditions would be required to create a just society. In this sense, he put the just before the good. Never mind what humans innately want from society, what’s important is how to ensure that this society is just.

So rather than insist, as the earlier contract theorists did, that essentially human nature fears violent death and the war of all against all and therefore turns to society to protect humans from each other in order to preserve life and liberty, Rawls does not really make any claims about why humans want to join society; again, he only presupposes that they do. Here I actually found one of Allan Bloom’s articles, “Review: Justice: John Rawls Vs. The Tradition of Political Philosophy” – helpful. Bloom writes:

“The state of nature demonstrates that the positive goals of men which vary are not to be taken seriously in comparison with the negative fact on which all sensible men must agree, that death is terrible and must be avoided. They join civil society for protection from one another, and government’s sole purpose is the establishment and maintenance of peace. This origin and end of civil society is common to the contract theories of Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau in spite of their differences. And whether they believed the state of nature ever existed or not, it was meant to describe the reality underlying civil society. Man’s unsocial nature and the selfish character of the passion that motivates men’s adherence to civil society limit the possible and legitimate functions of that society.”

Seen in this sense, it is a common underlying human nature that unites us in our desire for civil society – albeit in a negative way. It is less about the positive “ends” that humans may wish to attain from society, and more about the avoidance of the bad. On the other hand, Rawls says little about why humans want to sign a social contract, because he says nothing about an underlying nature:

“Rawls is very vague about the reasons for joining civil society and, because he does not want to commit himself to any view of man’s nature, it cannot be determined whether the attachment to society- -attachment in the sense of obeying its laws-is really so important for a man in fulfilling himself.”

In fact, Bloom suggests that humans would immediately break the social contract in Rawls’s arrangement – a feeling I very much agree with:

“Once we leave the “original position” and the “veil of ignorance” drops, the motive for compliance falls away with it.” From what I know of Rawls and the Original Position, I agree. Even if humans would initially agree to the Rawlsian social contract – which asks that all inequalities explicitly benefit the least advantaged – wouldn’t they then become born into specific situations and wish to begin hording money and power for themselves? (In other words, acting just as human beings always do and always have?). As Bloom dryly notes, “ . . . once the scales fall from a man’s eyes, he may very well find that his life plan does not accord with liberal democracy” (653). There would be no further reason for them to adhere to the contract under Rawls, which was a very bloodless, paper-thin, rationalistic agreement to a set of abstract principles that would surely be forgotten in the real world. As a result, Bloom dismisses Rawls as offering little more than “a sermonizing argument for the nobility of sacrifice to the public good.”

But what’s interesting is that Bloom’s view seems to contrast with Fukuyama’s several cryptic lines about the difference between the contract theorists and Rawls. While Fukuyama seemed to indicate that the classical liberals were somehow advocating, each of them, some vision of the good (compared to Rawl’s relativism), Bloom seems to believe the opposite – that the liberals believed no good vision of life could ever be agreed upon, and so to achieve political harmony, we needed to learn toleration. Bloom writes:

“The contract theorists took the tack they did because they denied that there was a highest good and hence that there could be knowledge of happiness; there are only apparent goods, and what happiness is shifts with desire. Men have always disagreed about the good, in- deed, this has been a source of their quarrels, particularly in matters of religion. The contract theorists tried to show that this factual disagreement reflects a theoretical impossibility of agreement. Out of this bleak situation which seems to make political philosophy impossible, they drew their hope. If the importance of all particular visions of the good can be depreciated, while all men can agree on the bad and their inclinations support its avoidance, then solid foundations can be achieved. But it has to be emphasized that a precondition of this result is the diminishing of men’s attachment to their vision of happiness in favor of mere life and the pursuit of the means of maintaining life” (653).

Then Bloom does seem to get at Fukuyama’s point – somewhat:

“Rawls, while joining the modern natural right thinkers in abandoning the attempt to establish a single, objective standard of the good valid for all men, and in admitting a countless variety of equally worthy and potentially conflicting life plans or visions of happiness, still contends, as did the premodern natural right thinkers, that the goal of society is to promote happiness. Thus he is unable to found consensus on knowledge of the good, as did the ancients, or on agreement about the bad, as did the moderns.”

So seen in this sense, the “good” that Fukuyama sees the liberals agreeing on is that man’s nature requires avoidance of the bad state associated with the pre-social state of nature. Rawls is even, if I am to understand, relativistic about this point. As a result, I find that Bloom’s explanation makes perfect sense to me, while I am somewhat forced to dismiss Fukuyama’s original point that sent me down this road as somewhat misleading. It’s not as though the liberals postulated specific goods for human aims – while Rawls was a pure relativist – except insofar as the liberals (according to Bloom) agreed on the most basic of ends – avoiding the worst possible scenario in a pre-social existence (a “war of all against all”). Rawls, instead of insisting that all humans do have a reason for turning to society (again, albeit a very low, base reason), Rawls presupposes agreement for the terms of society that he proposes. In doing so, it is not so much that he urges toleration for different, strong viewpoints, or that he tries to tamp them down, but that he doesn’t particularly take the seriously:

“Rawls, looking at the believers of our day in America, whose religious views are the fruit of Enlightenment thought, assures us that faith is no threat to the social contract and that Locke and Rousseau were needlessly intolerant. Thus he profits from their labors without having

to take on their disagreeable responsibilities. Hobbes, Locke, Rousseau knew that their teaching could not be maintained if biblical revelation were true and that there was no way to avoid confronting it directly. Rawls, counting on men’s having weak beliefs, simply ignores the challenge to his teaching posed by the claims of religion.”

All of this is a powerful, fascinating indictment of Rawls on the part of both Fukuyama and Bloom. Again, Rawls doesn’t seem to be who I thought he was – the preeminent philosopher of social justice morality; instead he sounds like the philosopher who justifies modern relativism in the name of self-esteem. I’ll surely have to read his work soon, particularly if he is as fundamental as Fukuyama says he is. I am still intrigued with Fukuyama’s point that most leading theorists are Rawlsian today, not classical natural rights liberals. To hear Bloom tell it, that’s because most of us take modern civilization for granted; the liberals, having had their effect on neutering strong religious belief, paved the way for Rawls (and the rest of us) to take it for granted that no one would really want anything other than liberal democracy.

This only underscores my belief that taking an ontological approach matters. One constant I am noticing in my study of different competing theories of philosophy is that the thinkers I admire most, the ones whose work seems most plausible, promising, and insightful are those with the fullest understanding of human nature – human beings as we are. Conversely, those thinkers whose work seems less plausible, and typically more dangerous, are those thinkers whose work either ignores the question of human nature, or whose work focuses on exploiting some aspect of human nature, while trying to suppress or permanently change the less desirable aspects. It sounds as though John Rawls may fall into this camp. I am thinking in particular of Karx Marx, whose understanding of human nature was a thin one in my view; and of Paulo Freire, Marx’s educational counterpart, whose (however obscurely) stated educational goal was “humanization” – the achievement of a kind of overcoming of human nature – in a very, very narrow sense.

One related tension here is the question of how, given a relatively fixed human nature, to pursue the creation of a better world, which is to say a better society. The thinkers whose work I most appreciate (Edmund Burke, James Madison and Alexander Hamilton, Adam Smith, Lev Vygotsky, and John Dewey, for example) are those who, in my view, understand best the restrictions of human nature, but inspire us to and show us how to live up to the highest aspects of our better natures, while keeping our lesser natures in check. The classical liberal code that Fukuyama and Bloom reference – derived from a deliberately low-sight-setting on the part of Hobbes, Locke, et al (the notion that all humans fear the death and destruction of living outside the state of nature) becomes the grounds for both individual, natural rights, as well as for the universalism and egalitarianism (“all men are created equal”) that is truly inspiring and which has inspired human beings ever since the Enlightenment. It is this marriage of clear-eyed ontological theorizing as well as plausible, inspiring moral or social (or educational) ideals that I look for most.

***

I have clearly gotten off track again. I know that I began by attempting to discuss Fukuyama’s assessment of the critiques of liberalism from the left and from the right, and I have barely gotten through the first critique from the left. Let me briefly say a little more about the other critiques from the left.

As I said, I don’t really buy Fukuyama’s broader point about the left’s focus on individual autonomy destroying public-spiritedness, although clearly his analysis of the problem led me to some fruitful understanding of tradition (!).

Fukuyama’s second point is that the left’s focus on individual autonomy actually resulted in the left – in the form of the critical theorists – beginning to attack the foundations of liberalism itself. I find this point certainly more compelling. Fukuyama cites a number of the critical theory left’s critiques of liberalism; most of them are familiar to me:

- Marcuse’s neo-Marxist critique that liberalism is a sham merely controlled by elites that has lulled the proletariat into being “bought off” – to the point that they have now become a “counterrevolutionary” class.

- A communitarian rejection of liberalism’s focus on individual autonomy – because individuals don’t really have meaningful choice, unshaped by race, gender, or other characteristics (that there is no original position).

- A critique of liberalism’s lack of focus on groups – liberalism tends to think of group membership as voluntary rather than involuntary, or fluid rather than fixed. It does this, because, again, that is the only way to avoid tribalism – you have to focus on the individual and the universal – but in doing so, liberalism misses the way that group membership really does matter (especially in the case of race, gender, etc.). This is a strong point.

- A related point to this is that liberalism doesn’t – but should – grant autonomy to groups; rather than assimilation, liberalism should pursue autonomy. This is a deeply complex but important point.

- A criticism that equates liberalism with either neoliberalism’s excesses, or with colonialism and imperialism; liberalism is simply one way of seeing the world that has been used as an excuse to dominate other views.

- A critique of liberalism that says it is too incremental in its reform

These are all very strong objections, particularly the objections about liberalism’s blindspots regarding group membership. Fukuyama attempts to answer each critique, and does so fairly well, with most of his responses coming down to the logical error of, as he puts it, essentializing historically contingent phenomena (83). In essence, liberalism was thought of and begun by biased individuals and societies, but the theory itself is not inherently a tool of these purposes. In fact, says Fukuyama, it is unique because it can *correct* these problems over time. Yes, it’s pace can seem slow, but this is a necessary safeguard; what happens, after all, if one’s enemies get power and are allowed to run untrammeled straight toward their own revolutionary updates to society?

In particular, Fukuyama’s response to the critique that liberalism has no inherent understanding of group identity is especially noteworthy. He makes an interesting distinction between “fluid” versus “fixed” categories of identity. Fukuyama argues that liberal social policies should seek to equalize outcomes based on fluid categories – he names class, for instance – rather than on fixed or innate categories, such as race or gender. This is due to several reasons. First, formal recognition of fixed group identity tends only to “harden group differences” (151). Second of all, for Fukuyama, differences of outcome between any groups are the result of such complex social and economic forces that they are often beyond the ability of policy to diagnose or to complete alleviate. His notation – fluid categories, in particular, made me think of John Dewey’s social-democratic ideal: a society based on individuals, all of whom are capable of belonging to groups in ways that benefit the individual and allow permeability between groups. This seems to support the ideal of having a variety of “fluid” groups as at least a social ideal.

The third argument Fukuyama cites – the final critique from the left – comes in a chapter Fukuyama titles, “The Critique of Rationality.” This was another fairly familiar argument to me – Michel Foucault made basically the same argument against science – whose mode of cognition is the core of liberalism – as Marcuse made against liberalism itself: that science is not an impersonal search for an objective truth that exists, but a sham – the attempt by the powerful to maintain power and to order the world in their chosen way, under the guise of objectivity. Instead there are many “ways of knowing,” with none more valid than another.

Fukuyama’s answer to this is solid and compelling: yes, there is a grain of truth to Foucault’s critique – often science has been a tool of the powerful, and yes, science is often not neutral but political, and it should be checked when it seems to try to impose something that is patently ideological and untrue. But says Fukuyama, the only plausible way forward – if we don’t wish to abandon the notion of objective truth (which would be deeply cynical) – is to insist science is checked by the liberal system itself – ideological claims masquerading as objective truth must be subjected to rigorous attempts at disconfirmation, through reason, induction, the scientific method. This, Fukuyama says, has happened many times through history. The only alternative is a cynicism that says all truth is relative, that power exists everywhere (“biopower” in Foucault’s terminology) and anywhere (rightly pointed out as a kind of conspiracy theory thinking by Fukuyama), and – as Jonathan Rauch would point out – typically the substitution of truth for pure political power (why after all, asks Fukuyama, should Foucault’s own motives be exempt from the same cynicism – isn’t he, too, just out for power?) and the attendant naked tribalism (which Fukuyama cites as already happening on the identitarian left as well as on the populist right – where Foucault’s same claims about science as cultural hegemony have been raised by right wing COVID deniers).

In the end, I thought Fukuyama’s points about the challenges to liberalism from the left – aside from the first one – were all well-identified, well-explained, and well-refuted. So much of the justification of liberalism seems to come down to the notion that it’s the best system that’s really available given the limited capacities of human beings. Science creates truth via an impersonal process that is subject to biases, yes, and which doesn’t recognize minority status, yes, but whose premises, when you think about them, are sort of the only realistic and peaceful way to settle truth (not to mention the most stunningly efficient). The individualism and universalism of liberalism are the political components of this liberal science – the best ways to ensure the peaceful maintenance of diverse, pluralistic societies that don’t splinter into factional groups. The incrementalism of liberalism, the protection of minority rights, the freedoms of speech and association for all – even the apparently backward or transgressive – are the only way to ensure that no ideological faction gains total authority. Fukuyama does well to sketch out these objections, and to answer them cogently.

I have run out of space and time to detail the objections that he characterizes as coming from the right – particularly those from neoliberalism. These are, if anything, much more potent and easy to understand than those from the left, because they are far more straightforward, and far more materialist. Let’s just say that it’s much easier to understand the problems that a Milton Freidman has caused liberalism than those of a John Rawls.

I will attempt to analyze those in a subsequent post.