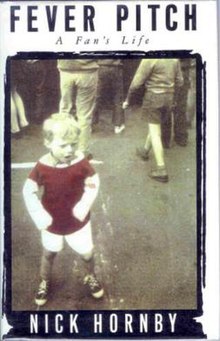

At some point during the pandemic, I stopped watching basketball and started watching soccer. Why, I’m not sure. I remember thinking that watching basketball games without fans was pretty strange, and somewhere around that time, two years ago, I started reading Nick Hornby’s Fever Pitch, and I switched over the Premier League soccer viewing and haven’t looked back. I’d been a Premier League fan as a child, but I frankly hadn’t watched much soccer since those early 1990s days. Frankly, I just liked watching football and basketball and even baseball quite a bit more. Every time I turned on soccer, it seemed like players were diving right and left, which turned me off (particularly during the 2006 World Cup, as I recall, which I also remember as something of a starting point and end point for my interest in the game during my 20s).

But for some reason — maybe it was Hornby’s rich evocation of his own coming of age in the North Bank at Highbury, the texture and color that a good book can suddenly add to an entire sport and era. Perhaps it was the quality of the modern game in the Premier League, which I quickly realized was breathtaking in every way. Or maybe it was something about the “material conditions” of the way I began watching the games: they were easily recordable on Hulu, a special treat to be savored at night, commercial-less, after my day of work and parenting were over. Whatever it was, I was drawn right back into soccer again for the first time in 25 years, and I really haven’t looked back.

What stood out to me this time was that there is something so aesthetically pleasing about the game, something so intellectually interesting about watching it. It’s free-form and organic, like basketball, but with infinitely more space and possibility and dimensionality. I found myself admiring the subtleties: the way players allowed the ball to run across their bodies before they touched it, the way they used space. There is a whole high-flown, intellectual blog post here about my observations and reflections on what makes soccer really and truly deserve its moniker of the “beautiful game,” but I’ll save that for another post. What I am thinking of instead is the way that — in Lev Vygotsky’s fascinating insight, which I’ve surely repeated before on this blog — our intellectual development can enrich and deepen our experiential development, and vice versa. One of the sweetest rewards of this period of rapid intellectual growth that I’ve undergone in my mid-to-late thirties, over the past four years, the effect of downing massive quantities of philosophy, is that I often feel as though I’ve got so many new frameworks with which to reinterpret the ordinary fare of regular life. It seems to me that when you hit on something in this way, it’s just the opposite of the ivory tower-notion of intellectual development; rather than isolate you further, what you’re learning only brings real life all that much more to life by deepening your understanding and helping you see the root of things, the nature of things, the divisions and particulars in that much greater clarity.

Or at least this is how it seems to me these days.

Several examples come to mind here.

I think of course of my favorite sports book, The Game, by Ken Dryden. I’ve surely written about this several times in the past on this blog. What makes it stand out is not even its wonderful, first-person evocation of locker-room scenes, on-the-bus scenes — which are tremendous. But it’s the depth of analysis that Dryden brings to it. His characterizations of fellow players are not only apt, but they have real intellectual depth to them. Friday Night Lights is another classic sports book that I love, and Buzz Bissinger beautifully captures not only the people, but the entire socio-economic and political circumstances with great depth and context and sensitivity. But in my view, there’s simply no comparison with the depth of analysis Dryden brings: Guy Lafleur “inventing the game” with his virtuoso skills, Larry Robinson once but no longer a “presence” — “limited, economic, dominant” with his offensive skills “an exciting appendage” — or Scotty Bowman, the brilliant coach about whom the players are ambivalent until their careers are over, or especially about the way the Soviets changed hockey (“a game of transitions”). I once heard a comment about one famous band: a fan was remarking on how creative and textured their music was, when another fan interjected something along the lines of, “Jazz-trained musicians playing rock — works every time.” It’s the same idea as how Dryden, an Ivy League history major and a trained lawyer, was able to write about the game with more depth and insight because, in a sense, he’d been educated as an intellectual to do just that.

Here is another example I love: It’s a classic 1967 clip of Leonard Bernstein analyzing contemporary rock music, particularly that of the Beatles. I’m not sure I’ve ever heard such penetrating insight regarding popular music. It’s Bernstein’s intellectual approach, his classical training and real musical knowledge (not to mention his gifts for communicating with a mass audience on television) that allow him to bring real perspective to music that’s by now so familiar. I was particularly fascinating by the section during which he characterizes a song by the Monkees by playing some of it himself on the piano, notes the song’s gospel influence (fascinating), and then highlights a particularly interesting chord change. But what makes the clip special is that he goes on to put this into a historical context: asking rhetorically, “What’s so special about that?” — sliding it up against music from the 1930s, from Duke Ellington and Gershwin, which he reminds us was far more inventive and sophisticated. “Ah, but that’s the whole point,” he says. This newer generation has rejected that music as too sophisticated, that of an “older, slicker generation — the old fashioned sound of the cocktail lounge” — and underscores that rock music uses an incredibly limited harmonic range, the simple triads of folk music. Still, within that limited range, it borrows widely from a remarkable array of influences, and gives voice to an enviable range of sentiments and expression.

I have not conveyed this very well, and you should really watch the clip, but the whole segment I found quite remarkable. What stuck with me the most is that this is just what Vygotsky was saying: the intellectual learning that Bernstein had done (the training in musical theory, the obvious literary education that allowed him to toss off phrases like “straining after falsetto dreams of glory,” the comfort with real analysis he’d developed) — it had liberated him to make more in some sense of his encounters with this music, rather than to restrict him. His great understanding had not impeded his enjoyment of this fairly simple, new music, but had only aided in helping him understand more clearly what he liked about it. And when he looked at the music, he saw so much more than anyone else, because his own intellectual training (and again, I use this in Vygotsky’s original, and fairly wide, understanding of the term) had only enriched and deepened his experiential encounters, in this case with a popular form of art.

I don’t think I quite ever understood the extent to which philosophy and poetry can unite in this way. I use both of those terms quite broadly, again. It’s the same hopeful sense of breaking down barriers that I first read in Dewey, in the chapter in Democracy and Education about vocational ed, in which Dewey reminds us that a vocation can be a calling, on the same spectrum as any “higher” intellectual activity, and just as worthy and valid, provided that it provides the opportunity for continuous growth.

***

I’ve thought about all of this with soccer. Like Dryden with hockey or Bernstein with pop music, I find myself drawn to this popular medium from an intellectual perspective, driven to understand what draws me to the experience of watching it. My own studies have taken me to several new frameworks: namely Aristotle’s concept of hylomorphism, and John Dewey’s concept of art-as-experience. I realize this sounds incredibly pretentious, but I’ve found it amazingly intriguing to learn these new intellectual lenses and to apply them to something as familiar and as everyday as the world’s most popular game. Hopefully in a future post or two, I’ll go in depth and explain what I find so interesting about these frameworks.