The older I get and the more I learn, the more I’m starting to believe that I may be an Aristotelian. Although I love and appreciate Plato’s sense of drama and allegory, more and more I find myself patterning my way of thinking on Aristotle: on his matter-of-fact classification, his breaking down of everything into categories, his slowing things down, his looking at the nature of a thing in itself, he careful, methodical approach.

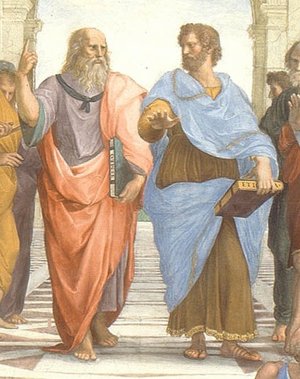

I have a poster in my classroom — that famous one, the “School of Athens” — Plato pointing up toward the heavens, and Aristotle pointing down toward the earth, and I enjoy telling students about the difference. I’m sure that most of them would side more with Plato the idealist, but I’ve become more of a realist as I’ve aged, as I suppose many of us do. But what I never expected was that I’ve in a sense become a more straightforward and even a *slower* thinker: I want to proceed more carefully, more deliberately, to think more clearly, to parse, to probe, to question. Measure twice and cut once — surely the hallmark of most middle aged men working on home repair projects, but mine all the same when working on intellectual ones. Aristotle, it is.

Not long ago, I was reading Theodore Brameld’s fascinating book, Patterns of Educational Philosophy — a truly mesmerizing work from long ago (but which seems amazingly current) that I’ll surely have to blog at length about sometime soon (and haven’t been able to since I read it months ago, I’m afraid). Brameld included one of the most striking summaries of Aristotle that I’ve ever read, and introduced me to a new aspect of his thought that I hadn’t come across in my college readings of the Ethics and the Politics: hylomorphism.

Hylomorphism, which translates into “form within matter” is the Aristotelian method of uniting Plato’s division of mere matter and idealized Form. In Plato’s world, as my high school social studies teacher taught us, every chair in the real world is just a copy of an ideal chair — one that does not and cannot exist in the real world, but only in an idealized state of perfection — the world of ideas, of the eternal Forms.

Aristotle modifies this otherworldly conception of Form by situating it instead in the real world. Form is still an ideal, but it is the culmination of the essence of every being. The form is located within the matter, as a kind of inherent potential. The famous example is an acorn: it holds within itself the form of the oak tree, and nature acts in a teleological fashion to promote this growth. It does not become a pine tree or a maple tree, because that’s not its form. The notion is that whatever a thing is in itself, that is what it aspires to be. For this “aspiration,” he uses the term “entelecheia” — quite literally “having its purpose within.”

Again, I am no philosophy expert, and I frankly haven’t read the actual Aristotle, but from my understanding of this concept, I find it to be a much more intuitive idea than Plato’s idealized Form, which seems particularly divorced from nature, something based on an ideal conceived in the mind of humans. It is also an approach that, coming from Aristotle, the man who virtually invented biology and physical science, takes into account the great diversity of life on this planet, and of the many and varied “forms,” surely, that exist, rather than the Platonic ideal, which seems more remote from the world.

It is hard for me to tell to what extent Aristotle’s form is an ideal or simply a finished product. In other words, is an apple that never quite ripens and develops an example of form, or mere matter? I think that he would say it is mere matter, that all matter of one essence *aspires* to be pure form, but not all objects or beings attain that.

As an educator, I spend much of my time contemplating the difference between actuality and potentiality, about development and growth, and about nature and nurture. In fact, it’s hard for me not to see everything this way — in the process of growing and becoming. What I find myself thinking about often these days, in light of learning about hylomorphism, is something that’s similar to Aristotle’s idea, but slightly different too. I find myself often asking myself, What is the nature of a thing in itself, and what are the inherent possibilities of it, given its nature? What is a thing aspiring to be by its form?

Or perhaps it’s more accurate to ask, what is the perfected form of a thing? It seems different, in a way, to ask what something is aspiring to be, versus what it is in its perfected state of pure form, doesn’t it? The former seems to impute a motive, a desire. In Dewey, it seems as though the answer always lying in wait is a kind of naturalistic developmentalism, a sort of a-moral belief that the aim of life is continued life, the aim of growth is continued growth, etc. Perhaps it is a kind of Darwinian entelecheia: that we are inherently wishing to survive, to continue life. In Aristotle, the best I can tell, it is his concept of the Unmoved Mover, the state of pure form itself, that impels all matter toward purer states of form, almost like a magnet. He does not create the world, like the Christian god — matter has always existed — but he starts its movement toward actualization.

Aristotle writes (and here, notice, I have just opened the Metaphysics!) that, “There is something which moves without being moved” and he compares it to the way something or someone who is desired or loved moves others. “The final cause, then,” he writes, “produces motion as being loved” (Metaphysics, 1072b). This is certainly a fascinating idea — the notion that we are compelled toward beauty not in a sort of biological, preserve-the-species sense, but out of an innate desire to fulfil our essence, which is the perfection of form, via the magnetic pull of the perfection of the Unmoved Mover, who Aristotle begins referring to partway through the section I read simply as “God.” It’s been some time since I’ve read anything that has seriously discussed God, much less something that has given such a frankly powerful defense and explanation is Him as this. One can see how Aristotle became so influential in Christian thought in the Middle Ages. And yet, what a fascinatingly different explanation for our instinctive love of beauty, whether in physical form, or in the perfection of art itself. It is as though we feel an instinctive pleasure in gazing at the perfection of Form.

Here it does seem that Aristotle is flirting with the Platonic dualism, setting up a remote god in another world who himself embodies eternal perfection. And yet, the whole concept of hylomorphism is still of-this-world: the perfection of each essence, is very much attainable and perhaps even observable on earth. It does seem less of an ideal and more of a “very, very good example.”

And again, I find myself thinking about this theory of the oak tree within the acorn often. What is the potentiality in a given form, what is a thing of itself? What is its nature impelling it to be? What is the perfected form of something?

I think about it, for example, with houses: what is each style of house trying to aspire to? What is its ideal, and what is it capable of being, or trying to be, by definition? What is the perfected form of the cape, for example? What is the perfected form of the colonial, the Tudor, or even a specific room — the den, for example? I am not talking about an idealized Platonic version that exists somewhere in my mind — some vague notion of the perfect room. But I am talking about something far more situational: what is the idealized form that everything aspires to, given its form and its function, and given its inherent nature — its restrictions and its medium and its distinctions.

Here is where I think about a sport like soccer, which I had alluded to in my previous post. What — given the nature of the game itself — the techniques that must be used (feet only, no hands), the physical restrictions (size and weight of the ball, size of the field, surface of the field, size of the goal), the technical restrictions (number of players, amount of time, the object of the game itself) — given all of this, what is the nature of the game itself? What is the form that aligns best with that nature? What is the form that the game is bending toward, the form that it aspires to be in its perfected state?

This seems different to me than describing the *possibility* inherent in the game, as people often talk about when they write about great advances in sport, such as the forward pass, or the way the Soviets began to play hockey in the 1970s. But saying that there is possibility inherent in the game seems to indicate that the game can become something new and unexpected. But that’s not really right. Rule changes aside, playing soccer in a different way, I think should be seen as moving closer to a kind of — not idealized form — but a kind of inherent form of how the game, given its limitations and its nature — can be played.

To be truly Aristotelian, perhaps one might also break down the game of soccer into different styles, each of which bends toward a pure form of itself. One might consider the purest form of, say, the more cynical style of “boot and chase,” of kicking the ball into the “mixer” — into the penalty box — and waiting to see what happens. Perhaps this approach has its perfected state, or reached it in some team. While on the other hand, perhaps the ball-on-the-ground, passing, linking of play form of soccer is shown in its purest form, elsewhere too. Or perhaps the later itself is merely the perfected state.

I think about this whenever I watch, for example, high school players. You can see the game is quite clearly on some lower plane of development. The passes are untidy, ricocheting of other players’ bodies; the players are clumped, not spread. It is only when you watch the very best athletes, the most coordinated, the most in-shape, and well-coached and -trained, that you can begin to see the game as it really is: its characteristics of space, of timing, of geometry. Once you remove the imperfections in the participants, just as when you employ good instead of faulty musicians, suddenly the nature of the piece of music, or of the sport, become more clear. What is the game in its perfected state? What is it by its nature, and what does it therefore aspire to be? What are its fundamental characteristics? And what is its purest form?

Somehow it is this notion of purity of essence that is so compelling to me nowadays, as I begin to think more philosophically and to pursue important questions in a more self-consciously philosophic manner. I’ve written before on here, a number of times in fact, about my growing desire to identify fundamental disagreements on the important questions of the world. And implicit in this desire is the desire to find the “purest” representatives of the most compelling and contrasting viewpoints. I want the strongest possible clash of opinions, and I want each side to be representing these opinions in their purest form.

It is the form within the matter that is so fascinating, because in the end this is what is so compelling for a philosopher: to determine what that form is, what the inherent nature, the true, fundamental nature of a thing really is, and what it is in its perfected and most stripped-away, purest state. That question compels philosophers by excitement — just like we’re all pulled by the Unmoved Mover.