I think I’ve posted in the past about my quest to read my way through some of the “classics” in education, and one of the few definitive lists I was able to find (which says something interesting) is educational writer Grant Wiggins’s, posted on his blog before he died. Last night I found myself poking around on his site and discovering, from the author of Understanding by Design himself, several interesting blog posts about the very topic I’ve found myself thinking a lot about while teaching during this pandemic:

To what extent should we as teachers plan (and how)? To what extent are educational experiences educative — if we had the ends and goals in mind ahead of time?

A little about Wiggins. I’d read Wiggins’s articles before, in addition to having read his books, landmarks in the area of curriculum and planning, Schooling by Design and Understanding by Design. I see Wiggins’s work as coming out of a long tradition, going back certainly to Ralph Tyler, of rational planning in education. Wiggins is pretty overt about Tyler’s influence. I’m interested to learn more about that path, the background and history of lesson planning, the rational sense of education. (Probably goes back to Aristotle, I bet.) What a shame that Aristotle’s book, On Education, was lost in the ages.

As for Wiggins, he is definitely one of those gadfly-type writers, a good polemicist, the sort of guy who always seems to be telling educators, “This makes no sense! A soccer coach wouldn’t just . . . A doctor wouldn’t just . . .” That whole vibe: half-outsider, half insider. Maybe was a teacher for a while, maybe not. (I can never decide whether having been a teacher makes these kinds of people more or less annoying.) Wiggins does have some depth to his writing, but he’s definitely not a scholar — he’s a classic PD leader, a workshop presenter, not quite pushing a product, but always pushing an approach. The dial is always set at a very low level of outrage, but it’s always about really nuts and bolts stuff like planning. His basic premise seems to be that teachers need to be more intentional about what they’re going for. It’s a premise I find myself agreeing with more and more, one I find more and more vital for educators.

Anyway, here’s an interesting post of his that I stumbled across from about eight years ago, called “UbD and serendipity: why planning helps rather than hinders creativity.” Just what I have been thinking about. Wiggins begins with just the nagging question in my head:

“A recent query via Twitter asked a question we often hear: isn’t UbD (or any planning process) antithetical to such approaches as project-based learning and inquiry-based learning, since you can’t and shouldn’t plan for an unknown serendipitous result? More generally, isn’t there something faintly oppressive and hampering of creativity in such planning approaches?”

His answer: “In short: no.” We plan for success in many other venues (classic Wiggins here): family life, music production, sports — in order to try to achieve good results in the face of challenges and unknowns. That is different than trying to script everything that happens. “A plan,” he writes, “is a framework for clarifying purposes and the best means of causing them, in order to achieve the most satisfying and appropriate outcome.” I think that point about clarifying purposes is particularly important.

Wiggins notes that many educators seem to carry basic reservations about whether planning kills creativity, a concern he dismisses:

You need multiple models to inspire and focus; you need deliberately-designed experiences to escape habit and formulae. Creativity by design is not a contradiction in terms, in short. As anyone who has ever attended a workshop run by IDEO or a class in acting or drawing, creativity is fostered and made more likely by some deliberate moves and modeling offered by master teachers. Mere free thinking doesn’t often yield much.

Could not agree more: sometimes it’s just these “enabling constraints” that actually liberate creativity. Not to mention that, as Wiggins says, real creativity often comes from working within the dictates of real structure and constraint:

On the contrary, creativity requires working with and through constraints: think of haiku and architecture – not to mention genuinely creative experimental science. Perhaps teachers who talk this way are simply compensating for the micro-management kids often face today at home and in school. But quality work rarely comes from just being given free time and no guidance or standards.

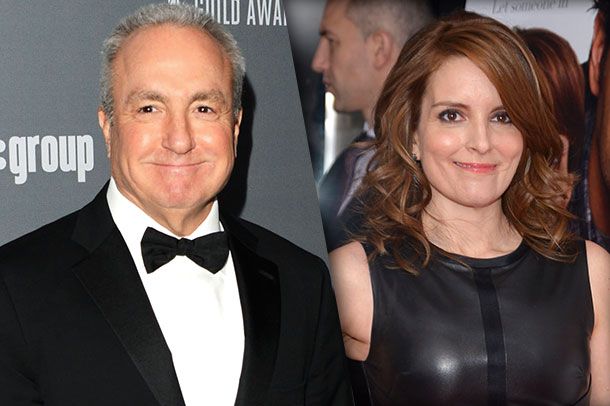

Again, it’s worth asking to what extent pure “creativity” in itself is actually a goal. I know that is heretical to ask, at least in English Language Arts circles, because it can sound tantamount to enlisting in the Arnie Duncan-led, Neo-con, NCLB-era high stakes testing sweepstakes. But there’s plenty of room, in real life, between unedited creativity and do-or-die drill-and-kill. I think here about Tina Fey’s account of Lorne Michaels, who once told her that being a TV producer was all about “discouraging creativity.” What he meant was that his job was to channel the writers’ and performers’ into a concentrated focus on serving the particular sketch, not only frilling-up the curtains on the set or indulging in weird costumes that would detract or unfocus the cast’s efforts. Yes, as Wiggins says, creativity is often sparked, not hindered, by constraints, but a good producer, like a good teacher, has to have his eye on the big picture goal. And in education, is unfettered creativity really the goal?

I think it’s important to understand what we mean when we talk about “creativity.” I think some educators mean that they wish students to “wow” them by creating something outstanding and outside-the-box. It’s difficult and hard work for educators to think ahead of time about what constitutes outstanding work on a given assignment. It’s particularly hard because, for example in English Language Arts, you’re often creating assignments that it’s hard to either locate or to picture models of. Recently, for instance, my colleagues and I created an assignment, not exactly unique, but somewhat new for us, called an “On Being” essay, in which students take up the question of self-definition: What it means to be . . . whatever it is they are. On being a (fill in the blank). You’d think this would be easy to find real-world examples of, but it’s not. It’s impossible. You can find examples of self-definition essays, but they’re not in the same format, which really makes a difference. And then you have the problem that all teachers attempting to use “real world” models face: too often essays written by professional adults are either hard for students to relate to or understand (because they are written from an adult perspective, often about topics that never go over well with a teenaged audience: stale marriages, being a working parent, or — God-forbid — the challenges of parenting adolescents). Often the structuring of these pieces is advanced or abstract when what you really want is a didactic example to show uncertain students something tangible to grab hold of. The goal isn’t exactly to show them the best that’s possible, but to set the bar just above their heads and to find some models that demonstrate clearly the techniques used to reach that bar. It’s harder to find these examples, and, in their absence, it can be hard to think of what you’re looking for too.

But it’s important to do that. Because what you’re really looking for, I’d argue, is not something that blows your mind open, and not something that absolutely conforms to a set, dead structure, but something that satisfies the authentic requirements of a meaningful assignment: the confluence of purpose, audience, and content. And those are things that you can (at least somewhat) quantify, and, even though it’s hard, picture and explain to students. In fact, I would argue, you have to. You have to plumb the depths of your understanding of the genre and assignment to locate the techniques that would create that outstanding assignment — then ask yourself how best to boil this down for your given group.

To that end, it’s not deadening to show students exactly what makes strong pieces of writing in a certain genre or for a certain assignment. It’s not confining of their creativity; it’s actually opening up options for them because this way they can understand, first, what constitutes good work, and second, what tools they can use to create that good work. Real creativity is not the goal — but quality writing, the intentional use of specific strategies. To have “real creativity” as your goal is to harken back to the notion of writing or creation as some magical act of conjuring. That is the opposite of what I hope to teach students about it — which is that writing is a form of craftsmanship, something that you can get better at through practice and through studying other writers, and through eliciting and acting on feedback.

An interesting related question is the question of models, which Wiggins takes up in a separate, linked, post. It’s the same question: To what extent does the use of models for educators limit students’ creativity? Wiggins starts the post talking about rubric, something that I too began my teaching career skeptical of, and really, am still somewhat skeptical of. He writes:

“But the most basic error is the use of rubrics without models. Without models to validate and ground them, rubrics are too vague and nowhere near as helpful to students as they might be.”

I agree with this point. Writing rubrics should not come first, as Wiggins says later in the essay. It needs to come after careful study of models by teachers and understanding by teachers of the components and characteristics — not of “what they want” (which sounds pedantic) but of what makes good writing for a given (reasonably authentic) purpose. Then, rubrics record and codify those characteristics, although I would argue rubrics are not the best way to present these characteristics to students, and a really only a scoring tool. But most importantly, they’re a place to gather and codify the important criteria.

Put this way, as Wiggins writes in the post — and this is a really, really important point, I think — it’s not as important that rubrics contain the most perfect descriptions (it’s okay, for Wiggins if they contain descriptors, such as “well-developed”), but that they are anchored in good models that illuminate what “well-developed” looks like. That’s important: rubrics really aren’t, in isolation, a good teaching tool. They shouldn’t have to be.

Perhaps though, that is is the most important thing to take away from this: we have to keep in mind that when we ask ourselves at the start of a unit, “What are we looking for?” that what we really mean is “What creates success on this reasonably authentic purpose?” (I say “reasonably authentic” somewhat ironically because, of course, we’re in school; though I truly do believe that the writing assignments I give students are all authentic because writing itself is a vital act of self-discovery, learning, and communicating. That is always entirely authentic and true.

But that’s really what this is — it’s not pedantic, it’s a process of inquiry to get to the heart of what constitutes success and then figuring out how to teach this to students. Is it valid to undertake this process with students? To purely discover it together? Yes, to pull out this knowledge that they already have is important to connect it with past experiences and to see where they are, but it is only a starting point for new teaching.

I start to wonder to what extent the magical, step-away-from-students-so-they-can-be-creative post goes back to Plato in some sense, back to the Socratic notion that you need to give students uninterrupted space so they open themselves up as honestly as possible to what they believe at the current moment — and only then can education have maximum value. The notion — I need to revisit “Meno” here — that we have this wisdom about is within ourselves, that we *know* inside what makes a good piece of writing, even in a foreign-to-us genre, because, let’s face it, we know — and it just takes a good teacher to bring that out of us. Believe me, I think this has a place — you have to see where students are coming from, and I am a big believer in those brainstorming sessions where you do a brain-dump of students’ prior knowledge on a given topic. What makes a good piece of writing? Sure, they have a decent idea by now. They’ve learned. But that’s only a starting point from which to teach them further components and tools, to add to their knowledge. And to do that, you have to have an idea of what you’re going for.

On that front, I think Wiggins is definitely right.