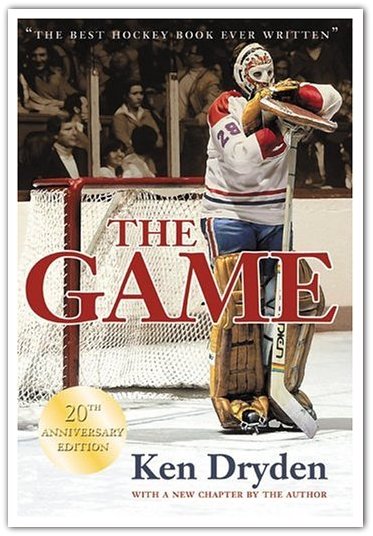

After the last few days of slogging through a mammoth blog post about a book that I frankly didn’t agree with much or even particularly enjoy, I thought it would be a welcome change of pace to write about one I do. That book is The Game, by Ken Dryden. I’ve probably blogged about this book before, but to me, prolific consumer of sports literature, this is very best one I have ever read.

Since I’ve been writing so much about education, I thought it would be interesting to look at The Game through the lens of an educator. What does The Game have to say about education? What are the implications that can be drawn from the conception of teaching and learning put forth by the book — one that is done at the absolute highest levels of excellence — professional sports.

I don’t know how interesting this post will be to anyone, but I think there’s a lot to be learned about education from looking at it in contexts besides schools.

Let’s look at the chief “educator” in the book — see what his goals are, what his teaching methods are, and whether he is effective — and what we can learn from him.

Educator: Scotty Bowman

Bowman is the wildly successful coach of the many-time champion Montreal Canadiens in the freewheeling 1970s. He is a national figure in Canada. Although the team contains many strong personalities and high-profile superstars, Bowman is very much, in Dryden’s words, “the boss.” He is depicted as a figure of immense respect among the players, though not necessarily a warm or inspirational presence.

Students: The Montreal Canadiens

They are three-time consecutive Stanley Cup winners at the time of this book, 1979. They are immensely skilled, and immensely diverse in their skills, as well as in their backgrounds and personalities. There are 26 players, all Candian, all of whom, to certain extents, were hockey superstars the entire lives. The majority of the players finished their formal education after high school, when they entered pro hockey. Dryden, who attended Cornell and law school, is an exception.

What is his goal?

At a big-picture level, Bowman’s goal is simple: to win the Stanley Cup. Anything short of this is seen as failure by the Montreal fans about by the Candiens themselves.

To accomplish that big goal, Bowman, like many classroom teachers, has two smaller goals when it comes to his “students”: he must instruct and he must motivate. However, compared to a teacher, Bowman’s need to actually instruct is small; his players already possess world-class skills. Instead, the majority of his instructional time seems to be focused on motivating his players during a long, demanding season, full of injuries, travel, and apparently meaningless games. His job is especially difficult because the Candiens are so talented and successful that they are always tempted to coast.

What are his teaching methods?

Although Bowman employs fairly traditional practice methods, Dryden specifically highlights three instructional methods in particular that Bowman uses: a combination of very, very traditional direct instruction, targeted, individualized feedback (often sarcastic and blunt), as well as less-than-transparent manipulation of a player’s “ice time.”

In one of my favorite passages in the book, Bowman uses classic lecture / direct instruction in his pre-game talk before a midseason home game against the mediocre Detroit Red Wings. In many ways, Bowman is the stereotypically dull classroom teacher: he drones on and on, making little attempt to engage the players, looking up at the bricks above their heads instead of at their faces. He has clearly not prepared his remarks very carefully — he leaps from topic to topic, sometimes mid-sentence. The players lose focus and begin making faces at each other and snickering. Bowman only gets their attention back when he becomes angry (“Put that guy down!” he bellows, referencing a Red Wings player) or inadvertently humorous. Dryden comments that in fact Bowman’s speech is less about specific strategy than about motivating his players to play hard against an inferior opponent.

Meanwhile, Bowman seems to be a master at individualized feedback — if you can call it that. Bowman again seems less focused on advancing his players’ skills than on motivating them to play hard or to follow his game-plans. While Dryden does not mention specific examples, it is implied that while Bowman is uncomfortable talking to the players, he is perfectly comfortable criticizing them, often doing so in a manner that is blunt, sarcastic, or simply so close to home that it resonates. He seems to understand each player so well that Dryden compares him to “a conscience that never shuts up.”

Some players, Dryden included, believe Bowman understands them, psychologically, as well as they do themselves. Dryden even starts to believe that because Bowman understands him so well, Bowman must be interested in him and wish to see him do well. But after speaking with Bowman later on, Dryden recants this belief — Bowman only has the team’s best interest in mind, not Dryden’s.

The last technique that Bowman uses is a kind of “assessment.” It is his estimation of a player’s ability that controls who plays and who does not. It is implied that Bowman is an astute judge of who plays well and who does not, although he is less than transparent about his reasoning. This puts many players in state of discomfort that Dryden compares to manipulation. Even Dryden, a star player, is benched for periods by Bowman and does not understand why.

While players do not “like” Bowman — and even regard the idea of liking such a man as preposterous — many of them, after their careers are over, speak effusively about how much he did for them.

To what extent is he effective?

Obviously, quite effective. The Canadiens go on to win their fourth straight Stanley Cup at the book’s end. Let’s look closer at each technique.

Although Bowman’s locker room speech is delivered in a dull manner, his analysis and strategy is penetrating and insightful, and his emotional message of motivation is clearly understood by the players. In a fascinating passage, Dryden talks about how after Bowman leaves the locker room, the players spend the next thirty minutes mocking what he said, but then, as the game draws closer, they begin repeating Bowman’s words to each other — this time in his tone. What a great demonstration of how wisdom gets through to reluctant students. It reminded me of a father telling his sons what to do: They are bored by him, they mock him, they resist . . . but they listen.

It’s not clear whether Bowman’s feedback causes his players to improve at hockey. Most of the breakthroughs that players have — such as Larry Robinson’s leap to topflight defensive play — come about through experimentation, rather than through coaching. That said, Bowman’s strategic planning — and his delivery to the team — is clearly effective. The Canadiens seem to play cohesively, in a variety of styles, against a variety of opponents who are both brutally physical (the Flyers), immensely skilled and fast (the Soviets), and deeply knowledgeable of the Canadiens’s weak spots (the Bruins). Meanwhile, Bowman’s motivational feedback is highly targeted and effective. Although the players chafe under his criticism, they clearly depend on Bowman to motivate them. Dryden suggests that Bowman’s chief insight is that players ultimately want to win. They can put up with not having a close personal relationship with their coach, as long as he helps them to win.

Implications for teachers

Appreciated Later On

Bowman is rarely depicted as teaching the game of hockey to the players; many of them are true experts and do not need skill development. On the other hand, he is shown to be both a talented manager and big-picture observer, adept at preparing for opponents and outside problems, while the players focus on their smaller areas of concern. In this way, Bowman is more like a good principal in charge of teachers than a teacher in charge of students. That said, Bowman clearly has more of a teaching and development role than a normal principal.

Bowman is clearly the kind of educator who, because of his nature but also because of his belief in doing what is best for the team, is not relational with his players, a fact that sometimes confuses his players, who are themselves mostly cohesive and familial. But this is a tension many teachers face: in order to do what is best for the students, sometimes this means you cannot be as personally close to the students. Yet you must also be careful not to be too distant, otherwise you risk not knowing your students well enough to know how to teach them best, or not eliciting the best from them — because most learners require at least some sort of bond with their teacher to really buy in to the process of learning.

Meanwhile, the effect of Bowman’s approach is that he is not a coach the players generally “like,” but he is the kind they think about later on, as a coach who has really “done a lot” for them. There are plenty of students who feel this way about teachers, too. Whether there are certain teachers or subjects that have this effect more than others is a good question. The classic example is the demanding teacher who is hated in the moment because of his high standards, his low course grades, or his gruff demeanor (or all three). Another example is the dry, dull teacher who makes little attempt to relate to students. (I remember one former student telling me that a coworker of mine “almost doesn’t have a personality.”) Bowman seems to be a blend of these first two types.

This sort of situation also implies that the teacher is giving the students education that is more useful in the long-term than the short. I think here of both content knowledge — such as the ability to punctuate, as well as the transferrable, content-less knowledge, such as the ability to manage your time or to study effectively. It’s something I think a lot about as a teacher: what kind of knowledge can I pass along to students that’s going to be helpful to them in twenty years?

What’s interesting is that there are other kinds of teachers who students remember as well, whose influence has less to do with lasting, foundational knowledge, and more to do with inspiration or personal connection. For example — the eccentric, passionate teacher whose enthusiasm for the intricacies of chemistry or ancient Greek history stays with her students years later. Or the one teacher who truly “sees” you as a person and helps you find your voice.

Part of what makes Bowman unique is the extent to which he understands his players as individuals: what motivates them, what excuses they will use, what their strengths are and their weaknesses to be improved. Good teachers have this ability too. They know their students as individuals. Here it’s important, I think, to distinguish between two types of knowledge though. First you have teachers who know their students as people. These teachers know their students’ backgrounds, families, hobbies, and other personal interests. Second you have teachers who know their students as learners. This is very different. This implies knowing a student’s academic skills — what type of writer a student is, what he struggles with, what his work habits are like. Sometimes this also implies knowing what motivates him, too.

The longer I teach, the more I am only interested in the first type of knowledge as it relates to the second type. While I try to build a class that allows students to incorporate their interests and passions — and which even allows students to actively process their own lives through creative writing — the time to me seems so short that when I talk to students during class or conferences, I want to — like Bowman — talk business. In a teacher’s case, that business is learning.

Teachers Must Care About Students, Not Winning

Bowman’s relationship with players is clearly different than the traditional teacher-student relationship. Bowman is not concerned so much with Dryden’s development in itself. He has, as Dryden suddenly realizes, no special feeling for Dryden, no special loyalty to his performance or improvement. Instead, Bowman cares only for Dryden’s development insofar as it helps the Canadiens win. If Dryden does poorly, he is benched, traded, or cut. The final goal is to win, and the coach quite literally uses the athlete to do accomplish this goal.

Unlike a coach, a teacher’s ultimate loyalty is to the individual student. His or her individual development is the ultimate goal — not the function this development serves the class or the wider school. Some teachers attempt to use students to achieve their own goals: such as being popular teachers, with many admiring students, or having the highest test scores. But ultimately teachers have no other goal besides their students’ learning.

Shared Goals

That said, Bowman and his players ostensibly share the same goal. Meanwhile, teachers and students, and students and their fellow students, do not. Sometimes they try to. Skillful teachers design classroom environments that encourage communal participation and shared goal-setting. One example of this is the famous math teacher, Jaime Escalante, who overtly modeled his classes on sports teams — with the Advanced Placement test representing the big game — the implicitly racist, biased Educational Testing Service, as well as the doubters in the broader society — representing the opposition. Only by working together to make each other better at math could the students succeed on game day. Other teachers employ class- or team-based projects. But building a real communal spirit and sense of shared purpose is rare in classrooms, and much harder than it looks.

There are structural reasons for this — many students are with different “teammates” in all eight of their classes each day. Then there is the inherent competition of grading and grade point averages — the market-based society in which schools operate to sort or select students.

The one broad exception I can think of is in schools that prioritize the school’s standardized test scores. In this sense, the whole class needs to perform well, sometimes the entire school. These schools are usually urban charter schools who make it their explicit mission to achieve high test scores. Some of these schools do succeed in cultivating a sense of community around a common academic goal — again, sometimes school-wide.

Some of these schools even “trade” or “cut” students, usually very implicitly, by implying, formally or informally, that students who do not perform academically should leave the school. That said, such approaches are controversial at best — once again, a school’s function is not to raise test scores for its own gain, but to raise the achievement of all of its students.

Feedback

That said, Bowman clearly knows how to maximize each individual’s performance. It’s a lot easier to get more out of a player than to cut or trade him. Bowman does this in part through his acute psychological understanding of individual players. He utilizes blunt criticism and even sarcastic barbs as formative feedback, and he sees to understand both just what to say to motivate them, and how much he can say to different players to elicit everything he can from them. This is something you read about in great coaches again and again: even reserved coaches like Bowman who are not particularly relational know their players as distinct individuals and treat them as such. This is something that skillful teachers do as well, all the while balancing the need to treat all students the same at a basic level of fairness.

Conclusion

I really can’t believe I wrote this much about just Scotty Bowman. I’d also wanted to look at the section on Guy Lafleur. Clearly that will have to wait for another blog post.

What’s interesting is that Ken Dryden wrote an actual book about education in Canada (I am forgetting the title right now). I bought and read it last year, but I don’t remember much about it, other than it wasn’t that interesting.

The last thing I want to note is that I wish there were more literate athletes writing first-person, ghost- or co-writer-less books. Especially ones who had thought as deeply about their teammates, coaches, and their sport as Dryden. The book in itself is quite honestly, in the end, a testament to Dryden’s own level of education.