One of the bright spots of all this social distancing is that I’ve been able to indulge my inner book nerd. It’s that side of myself that would happily — given a nice cold, grey, sun-less, snow-less, rain-less day — curl up inside the library on some sumptuous leather chair with a stack of books (and these days, if I’m to truly confess, a yellow legal pad and a pen).

Before we were kicked out of society and sent home, I went on the kind of book-run I haven’t done in years. I raided the shelves in the university library, in my school library, even in one of my coworkers’ classrooms. I’m still worried I’ll run out. There’s a word for this: abibliophobia. The fear of not having enough books.

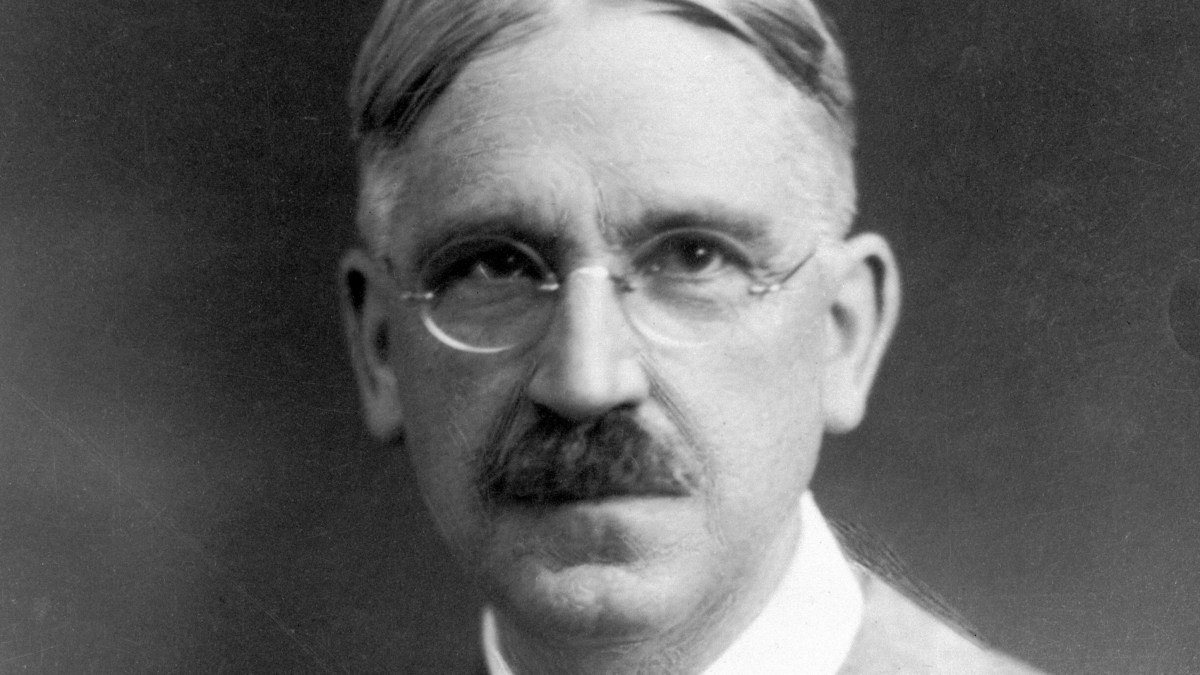

One of the most provocative titles I grabbed and one of the first I devoured was “The Child and the Curriculum” by famous American educational philosopher John Dewey.

Now, John Dewey was not a great writer. And I realize that byzantine educational tracts, first spoken to scholarly societies some hundred-plus years ago, and filled with all the wildness and intrigue that copious references to Jean-Jacques Rousseau and the Platonic dialogues call to mind are not exactly the sort of thing you go talking to your friends about. In fact the other day I was taking a “social distancing walk” with a neighbor and talking — in one of those Coronavirus, stuck-at-home, Tik Tock-just-doesn’t-cut-it-anymore moments — about what books we’re reading. When conversation turned to me, I didn’t even mention the Dewey binge. Just didn’t want to go there. I think I made something up: “Yeah, I’m reading that Hate U Get book, or whatever. Super woke. Love it.” You can’t go around telling people you’re reading educational philosophy. Even by the standards of Coronavirus socializing, that makes you pretty boring company. Especially when you’re talking about John Dewey, who was one of the most obscure writers ever to stretch a sentence beyond its reasonable length. I’ve been reading Dewey for months, searching for the wink of an eye, the faintest irony, the slightest rhetorical chuckle from the Pragmatist Sage. So far . . . nothing. It’s just like my Zoom Meeting outfit these days (from the shoulders up): All Business.

But . . . If you are daft enough to consider reading John Dewey — and let me just be clear: John Dewey is actually really, really worth reading — the place to start is with the book I just finished: “The Child and the Curriculum.” Let me tell you why it’s so worth reading.

First of all, it’s not really a book. It’s only thirty pages. Second of all, it’s by far the most accessible Dewey. Want to really make someone want to quit reading? Try giving them “Democracy and Education.” Students complain that they don’t like the contemporary novels we read in schools, which are basically all just sex and lies and body issues. I want to give them a copy of “The School and Society” — that’ll make them life-long non-readers. I have spent months trying to digest the rest of Dewey, which I’ll write more about in due time (Lord, help me), but “The Child and the Curriculum” I wolfed down in a single sitting.

It’s really, really interesting. Like all classics in any genre, it’s contemporary. It’s news that’s always news. It’s relevant. That’s just the word, in fact, that comes to mind about this book: Relevant. We’ve spent the last however-many years in education trying to make education Relevant to kids. In fact, I think at one or various points, that’s been an actual Movement in education: Relevance. You have to Relate the material to students. They have to See Their Lives in it. You have to Bring the Material to Life for these kids who, you know, don’t really “read books nowadays,” or “talk to people face-to-face anymore.”

All that Relevance talk? That’s Dewey. It all comes back to him, it all comes back to this 30-page book.

The basic idea of the book is a Dialectic. You take two ideas and contrast them and try to come to a reasonable conclusion. For Dewey, the two sides are:

1. The Subject Matter is Everything people (aka the Curriculum)

2. The Child is Everything people (aka the Child)

According to Dewey, they’re both right . . . and they’re both wrong:

Why the Curriculum People are Wrong

The first ones are wrong because subject matter — what Dewey calls “the old” teaching — is boring and remote to kids. Sure, we’ve heard this over and over again. We probably said it ourselves. It’s cultural by now. It’s deep in our DNA, and it was passed on to us from a lot of places, especially the Romantic tradition, which Dewey cites as specifically coming from Rousseau’s Emile.

But Dewey attacks the Subject Matter people even more subtly. His critique is that education is a process for growth. And that the best way to get students to grow is to understand the soil they are growing from — what experiences they’ve had, what interests they possess — because that’s the only way to give them A) Passion for Learning, and B) Learning that will stick. Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development hovers close by here.

Why the Child is Everything People are Wrong

This is interesting. Dewey goes after these people hard — which is interesting because for many years, even to this day, he’s sort of grouped in with them under the banner of “Child Centered” or “Progressive Ed.” But he’s not a Worship-the-Child guy — not at all.

He criticizes this approach — which he calls the “new education” because it treats children’s interests as “something finally significant in themselves.” No, says Dewey, they are not. They are “fluid and moving. They change from day to day and from hour to hour.” Instead, “their worth is in the leverage they afford.” If we simply allow a child to develop naturally, helter-skelter, she is doing little more than continually “starting . . . activities that do not arrive . . . It is as if the child were forever tasking and never eating.” This way, they’ll never develop, they’ll never grow.

What’s the Third Way, then?

This is where Dewey — in his super-dry, professor-speak — was onto something. According to Dewey, the teacher’s job is to “psychologize” the subject matter. What he means is: Bring it to Life! Make it meaningful. Make it Relevant.

Dewey: “His problem [the teacher’s] is inducing a vital and personal experiencing [of subject matter.”

He’s not exactly quotable.

Teachers should be concerned with, “the ways in which that subject may become a part of experience; what there is in the child’s present that is usable with reference to it . . . and determine the medium in which the child should be placed in order that his growth may be properly directed.”

A student must see, “how his experience already contains within itself elements . . . of just the same sort as those entering into the formulated study . . . how [his experience] contains within itself the attitudes, the motives, and the interests which have operated in developing and organizing the subject-matter.”

Teachers must be concerned with subject matter “as a related factor in a total and growing experience.” He even uses the word career: “The adult knowledge is drawn upon as revealing the possible career open to the child.”

You can see that when he writes about teachers and students, Dewey has to fight a tendency (a fight he often loses) to write about human beings like they are plants or “species” — part of some biological growth process. There’s a lot of botanistic diction in here: Give children who need to “operate” some “stimuli” in order to “develop” and “material” to “exercise” themselves. The school he founded was called the Lab School, after all.

But this is philosophy, right? It’s supposed to be oblique, it’s supposed to be up-at-10,000 feet. If you wanted something “clear,” go read “Teaching Like a Fucking Champion” or whatever book written by some Change Agent. This was 1902.

But . . . this is pretty revolutionary, influential stuff. You can see what Dewey is driving at: both extremes are bad — leaving the kid alone to develop, or forcing the kid to memorize arcane facts. Teachers should have a strong knowledge of both content, and, it seems to me, career possibilities, in order to meet students where they are, relate the material to them, and not so much nudge them toward growth, as free them to grow: “Guidance is not external imposition. It is freeing the life-process for its own most adequate fulfilment.” Teachers should be the Guide-on-the-Side.

The Problem: How do you do This?

The problem with this is, of course, that those momentary interests that students have, which Dewey writes about, those fleeting moments of dawning comprehension or turning-toward-of-interest, focusing all their being on one pursuit (dinosaurs! The solar system!). Dewey captures it well:

“Some of the child’s deeds are symptoms of a waning tendency . . .. Other activities are signs of a culminating power and interest; to them applies the maxim of striking while the iron is hot. As regards them, it is perhaps a matter of now or never. Selected, utilized, emphasized, they may mark a turning-point for good in the child’s whole career; neglected an opportunity goes, never to be recalled.”

I take it back — maybe Dewey can write.

But the problem with this, of course, is that responding to individual students in this way is . . . very individualized.

How do you do that in a classroom with twenty students who are in sometimes radically different places?

And Dewey is not just talking about responding to individual abilities by giving some students remediation and others enrichment. He’s talking about responding to individual interest — as in, some students would presumably be really into fossils and others would be working on learning the guitar. Somehow they’re both learning . . . science? That’s a tall order?

So how do you do that in one classroom?

How do you do that in a whole school?

We’ll — it’s been done — quite well, in fact.

That’ll be my next post.