Pragmatism: Provisional Truth, or Relativism?

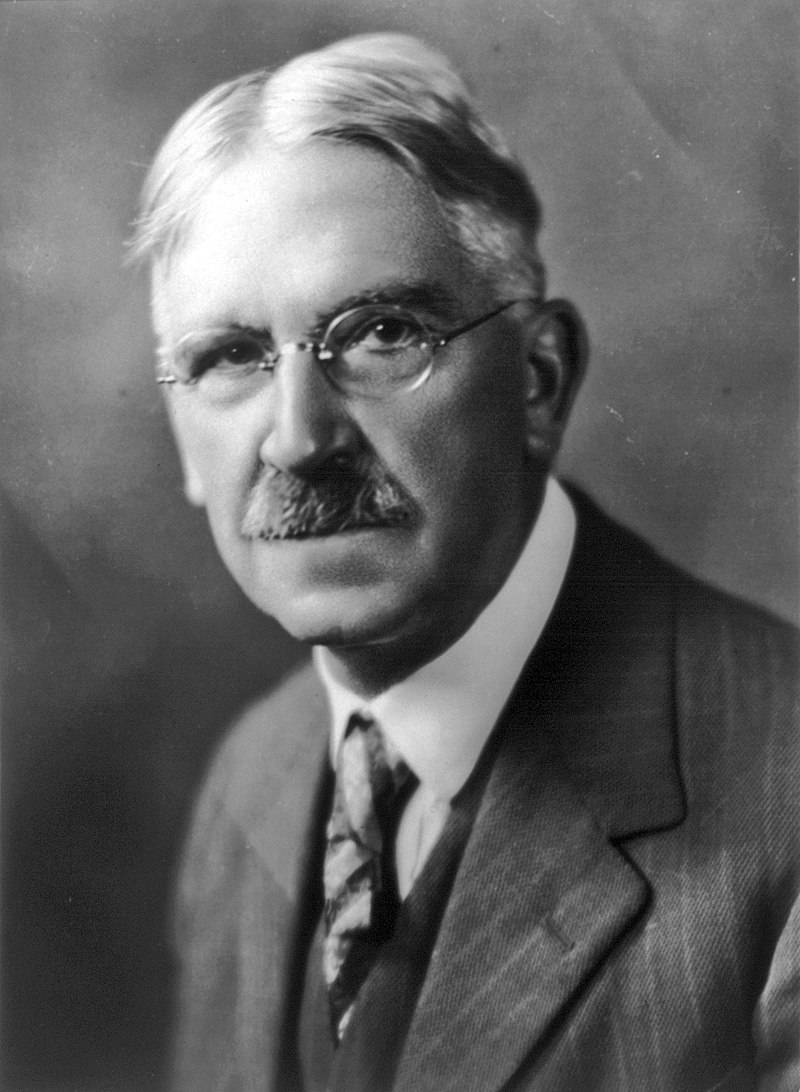

I’ve just started reading Dewey again. This time – “Human Nature and Conduct.” Given my current interest in all things “human nature,” this seemed like the right choice. Reading this book – which I’ll write about more at length once I’m done – has given me a new perspective on Dewey the Pragmatist. It has got me thinking about Dewey beyond his educational views, which are important, but seeming him more in his philosophic context. And, frankly, it has me asking some new questions about him: For instance, is Dewey a relativist, a historicist? Does he really believe in truth, or even the scientific approximation of truth – or just a shallow notion of “whatever works”? Does he, as a Pragmatist, believe that reality is so changeable that truth is therefore changeable? I’ve long admired Dewey’s educational thought, but now I’ve started wondering: Are there epistemic or political underpinnings of his educational philosophy that should concern me?

It all started a month or two ago as I was reading a book about the major challenges to American constitutional thinking. In one chapter, devoted to Pragmatism, there was an extensive analysis of Dewey’s challenge to the Lockean tradition of natural rights. According to the author of the chapter, James H. Nichols, JR., Dewey’s political goal is not Hobbesian self-preservation, or Lockean protection of sanctified natural right, but the ideal of growth for its own sake: more testing, hypothesizing, adapting to the environment, and improving. Growth leading to further growth, as Dewey put it in many of his best educational writings. Nichols equates this with Aristotle’s definition of the good life as activity, but without the notion of a completed, perfected state of the ideal man that such activity may attain, and which accompanies Aristotle’s conception of humans as a distinctive and unchanging species with fulfillable ideals. For Dewey, it really is about the process, since there’s no ultimate aim, no final end point, no ideal “good man” or “good life” that one can aspire to, other than the fairly loosely-defined one of experimentalism and pragmatic problem solving, which is by definition of-the-moment, and therefore historicist (the ideal conduct in one era is necessary different than that in another one because times and situations change).

When you come across Dewey’s idea in, say, Democracy and Education, it’s pretty inspiring: the notion that the end of education is to produce what we would call now, “life-long learners.” The end of education is more education; the end of your growth is more growth.

But when you think about it, it’s pretty agnostic, and frankly a little hard to accept. Nichols sees it as historicist, following Hegel – the notion that we always adapt to our era and to the particular problems; that we are always responding and adapting to a changing reality that is also changed by us. Nichols says that Dewey’s ideal of growth is not exactly a “natural” notion of growth – in the sense of Aristotle’s oak-in-the-acorn hylomorphism – instead it is a “Darwinian” nature – man changing and being changed by (and evolving within) his ecosystem (of his historical era, etc.).

One of the big issues with this concept of growth is how to define whether it’s positive or not. After all, it’s something Dewey lauds as his educational ideal. Yet – is it ideal? Cancers grow. So do evil empires. Same with egos – and so on. Growth isn’t always good. And it’s hard to imagine how Dewey’s concept – growth leading to more growth – becomes moral without escaping into some notion of fixed right and wrong. He does try to answer this, as I recall, in Democracy and Education – by distinguishing between good and bad growth in the example (as I recall) of a band of thieves: the education they offer is poor because it doesn’t lead to real growth (which is defined as the ability to interface with more and more groups beyond their own). Their education is bad – not necessarily because it violates a society’s moral code – but because it doesn’t allow their members further opportunities for fruitful connection with others, which is another way of saying it doesn’t allow the kind of pragmatic problem solving that is at the heart of Dewey’s political goal of growth. It’s interesting now to think about those passages that I loved in this new light of Dewey’s apparent moral agnosticism; it’s clear that in this case he is inserting some kind of moral belief – more growth (and all that leads to it) is good, and all that does not (including a fixed notion of beliefs) is bad. As he puts it, “growth is the only moral ‘end.’” But it’s hard not to think that he’s skirting around a lot of hard questions about morality and political ideals when he says the band of thieves aren’t bad because they’re amoral or breaking laws.

But Nichols reminds us, too, that if Dewey’s main insistence is that good growth is that which permits more growth, then we do fall into a kind of notion on of survival or perpetuation as the real goal. After all, if your goal is to get a plant to grow, rather than decay, your real good would be said to be trying to keep it alive. Even if Dewey’s educational vision of adults continuing to learn seems inspiring, at the end of the day it does have more than a slight whiff of the “use it or lose it” school of thought: the moment that you stop growing, you start dying. After all, who says that a good education can’t result in someone who does the same career for many years, without changing, or changing perspective on it; they simply enjoy it, and contribute to society. But there is no further “grow” – is that a poor education that produced them? Clearly not. Dewey’s system, since it steadfastly rejects true “ends,” can be said to reject the idea of true “maturation.” It’s more about a constant growth to maintain life – survival. Once Nichols makes this link, he says, we’re back in Hobbesian survivalist country, in which the goal of the social contract, perhaps, is to enable man to survive by adapting to his changing environment. Again, this seems strange given Dewey’s apparent commitment to some higher ideal of social planning and social improvement; but at the end of the day, even his commitment to equality is tied more to his belief that freedom is good because it expands the innate capacity of experimental problem solving, it releases more “energies” in Deweyian terms – rather than as an innate good in itself.

Nichols highlights just this tension in Dewey’s skepticism toward the Lockean natural rights doctrine of the founders, which Dewey apparent explicitly critiques in several of his works as something taken on faith that needs to be tested against everyday reality. That’s shaky country, for Nichols (and in my opinion, too). But again if you subscribe to no innate values, and believe there’s nothing inherent about human morality – that it’s all only custom or habit or natural impulse – you really have no reason to hold any particular truths about the innate worth of human beings as “self-evident,” as the founders did, following Locke. And then if the theory of natural rights is off the table, social planning has the ability to run roughshod over individual rights – and we all know where that particular vision can lead. It’s a less attractive side of Dewey, for sure, and one that gives me some real pause.

And to return to Dewey’s conception of growth, I think it is interesting, too, to contrast Aristotle’s eudaimonia – the good life, or highest life possible to live – with Dewey’s ideal of perpetual growth. Clearly they are both interested in an ideal that is activity, not stasis. Dewey’s vision of an “end” for humans is really a kind of ongoing growth in terms of our ability to – as he might say – adapt to our environment: to react more and more adroitly to the problems or challenges that arise in the present moment. In Dewey’s terms, growth consists largely in our ability to better make use of “experience” – the issues confronting us in the present moment. Aristotle on the other hand says that because humans are distinctive as a species, there are certain key functions that make us uniquely human, and our ability to demonstrate virtue (excellence) in them is what makes us get closer to the ideal of what humans can be – the living of the good/happy/blessed life (eudaimonia). Virtue is not easy to achieve, and requires learning and instruction, but there is a definite, fairly stable end that we can possible strive toward – both intellectually and morally.

I have to say, although I critiqued Aristotle’s notion of the good life in a previous post, I find myself rethinking that attitude. When you step back from it, you realize that his basic notion of the human ideal is actually pretty hard to argue with. Yes, I contested the idea that his view leads to happiness, but when you do take it instead as the ideal and “best” way to live (which admittedly is probably more what he is going for), it’s pretty hard to think of something too much better. And when you compare him side-by-side with Dewey, it’s hard not think that perhaps Dewey – and I can’t believe I’m saying this, committed Deweyian as I’ve seen myself for some years now since I first read him – may come up a little short.

After all, doesn’t Aristotle’s ideal, when you think about it, contain Dewey’s, in the way that a wider system contains a smaller one? Doesn’t just one of Aristotle’s single concepts – his notion of practical wisdom (phronesis) – sort of explain . . . everything in Dewey’s whole system? Isn’t Aristotle’s simple notion of a capacity not for intellectual wisdom but for understanding how to act in unique and different practical, everyday situations pretty much exactly what Dewey is spending so long trying to convey to us in the most abstract and confusing terms possible?

Alright, that’s probably not entirely fair, of course. I suppose the difference is probably that Aristotle saw a higher form of knowledge – wisdom, or intellectual knowledge – as that which is unchanging, because Aristotle saw a universe that was fundamentally unchanging. Dewey on the other hand sees the world in Darwinian/historicist fashion as ever-changing and deeply complex, so he never really saw capital-T Truth as something achievable or even particularly desirable to aspire to. But Aristotle didn’t see practical wisdom as aiming at a perfect knowledge either; his focus was, like Dewey’s, on a kind of situational understanding of what’s right, which Aristotle explicitly tells us – in ethical and political matters, anyway – precludes some enduring notion of total capital-T Truth. So again, this is right in line with Dewey, and on this ground, it does seem possible to read Dewey’s whole program as a kind of small branch on a much larger and more stable Aristotelian tree.

At one point in one of his famous education books – I think it is Experience and Education – Dewey says that it’s not necessary for adults to have pictured the ideal society before they can educate students for that society. Instead, all they need to do is to prepare students to be good problem solvers, communicators, industrious producers, and good collaborators; they must only teach students to be prepared and engaged, and then, surely, these students will be able to meet the challenges of their own eras. It is hard to accept the agnosticism in Dewey, which is frankly everywhere once you start to look for it. I guess I just see life and reality as too inherently stable to fully buy Dewey’s fully provisional notion of all truths. Maybe that is just psychological in me (or in all of us?) – the need to latch on to some sort of stability?

Either way, I’m excited to finish reading Human Nature and Conduct, and to write about that book shortly, too.