***

Being a parent must be hard nowadays.

In addition to having to worry about online predators, cell phone addictions, and an Oval Office resident who is basically a 70 year-old poster boy for every behavior we hope children shed by the time they’re seven, you’ve also got to worry about American corporations trying to drive you insane.

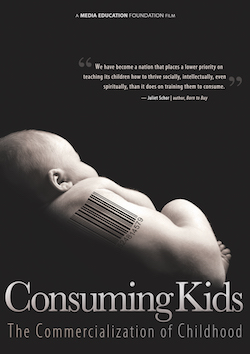

This past week I showed a fascinating, scarring documentary called “Consuming Kids: The Commercialization of Childhood” to my Media Literacy class. Although it was made back in 2008 and although I’ve seen it before, it has somehow become more revelatory for me with time. Here’s the basic premise: babies are born innocent and pure . . . until the ad industry gets hold of them. Then they try their damnedest to turn beautiful children into hysterical consumers lusting after an increasingly expensive parade of mindless games, toys, and junk food.

In a spellbinding scene near the start of the film. a child throws a temper tantrum right in the store when he can’t have a toy. What’s remarkable to me is not the behavior. There’s something more pernicious at play. That kid’s meltdown isn’t just random: it’s the calculated result of specific marketing techniques. The film describes these. Some of them are shady. Some of them you should probably go to jail for. Here are a few highlights from “Consuming Kids”:

–You Have to Get ‘Em Early. Children younger than five are learning brand logos before their ABCs. Don’t believe me? Watch this video. It’s cute — but also sort of heartbreaking to think a child’s first words might be not “Mama” or “Dada” but “Starbucks” or “WalMart.”

–Children are high rollers. Even though they don’t have “jobs” or “incomes” or even “the ability to form complete sentences,” according to the film, children in 2008 were responsible for influencing $700 billion per year in spending power. That’s billion. With a b. One recent estimate puts that figure at $1.2 trillion.

It’s hard to overstate how significant that is. According to the film, kids heavily influence a number of household purchases: food, clothes, even major stuff like cars. I guess that’s hardly news to anyone who has kids, but when you stop and think about it, it’s INSANE. You have incredibly impressionable, barely-informed consumers influencing HUGE amounts of money. But no need to worry — they’re only spending increasingly large amounts of unsupervised time on their phones and the internet. No need to worry!

Bottom line: Today’s kids are sitting ducks for unscrupulous marketers.

–Child advertisers basically want to drive parents insane. These MBAs hold conferences in lavish resorts and circulate peer reviewed journals devoted to subtle sales techniques such as “inciting kids to completely lose their shit.” Actually advertisers have a technical term for this: “pester power” — which basically means making your product so ridiculously appealing to kids that they WILL make a scene if they don’t get it and parents WILL have to fork over money to buy it.

–I guess I always thought that kids’ cartoons were purely entertaining. I never realized that companies are actually cashing in on Scooby Doo to sell crackers, or Spongebob to sell pasta. There’s another heartbreaking scene in the film: a cute little child is hugging a box of Spongebob-shaped macaroni to his chest, begging his parents to buy it.

“How do you know it’s better? You’ve never had it,” his father says.

“I just know!”

If exploiting kids’ favorite characters to sell them overpriced pasta isn’t sort of sad / wrong, I don’t know what is. (Then again, companies use cute puppies to sell products all the time.)

–The Infamous “Blink Test”: Now we get into the truly horrible stuff. The film shows how some marketers conduct “blink tests” — they strap a kid down in front of a television and record how many times he blinks during a commercial. I guess the goal is to create a commercial so mesmerizing that children won’t blink at all. That sounds messed up. Being forced to stare at a light without blinking? I might be wrong here, but wasn’t that what Stalin did? (And didn’t he only do it to grown men?)

–Then there are the downright creepy ethnographic studies that have researchers observing kids everywhere: in the grocery store, in their rooms, even in the bathtub or shower. Apparently their goal is to study kids so thoroughly that they can create endlessly educational products that improve kids’ lives . . . Wait, they’re just trying to create shampoo bottles in fun shapes that kids will make their parents buy, or else they’ll throw a fit.

Apparently when an ad researcher follows kids into the bathroom, it’s called an “ethnographic study.” When anyone else does it, it’s called “jail time.”

If all this wasn’t depressing enough, then there was the stunning revelation that not only do most kids’ websites and even video games contain layer on layer of advertising, but children’s movies contain something even more devious: product placement. That’s right: movie executives will slip in, say, a trip to WalMart in their kids film, all because WalMart slipped in a few extra hundred thousand into the film budget. Before you know it, you’ve got something like the Lego Ninjago movie, in theaters right now. It’s basically an entire film about a brand. Lego kits for practically every scene or character in that movie are up for sale. Plus, McDonald’s puts these toys in their Happy Meals. So “Mc-Danks” (as my students call it) is cashing in by having film-loving kids flocking to their counters, but the filmmakers are cashing in on the exposure: every McDonald’s in the land is commercial for their movie. And then Lego is getting paid twice.

This isn’t even as bad as last year’s release — the Lego Batman movie even featured product placement for outside companies like Chevy in the movie. Nice.

How saturated are our kids in advertisements? Makes you want to move to the woods and live in a cabin!

In fact, it made me think back to my own childhood and almost wish I had. It’s a little disorienting to think back on some of my childhood films and the implicit consumerism or out-and-out product placement featured in them:

–“E.T.” was product placement by Reeses, who wanted to promote their new candy, Reeses Pieces. The movie had initially approached Hershey, who declined to let them use M&Ms. Talk about a missed opportunity.

–“Back to the Future,” might as well have been one long commercial: DeLorean, Nike, Pepsi, Texaco, Pizza Hut, Toyota . . . the list goes on and on. Apparently the so-blatant-that-I-still-remember-it-as-weird advertisement for California Raisins on the park bench in the film was so over-the-top that the company demanded its money back.

–“The Mighty Ducks” was a heartwarming tale of a group of low income hockey kids whose miraculous turnaround only happens after they become sponsored by a law firm and are sent on a brandname spending orgy at a sporting goods store. The second film, “D2” gets right to the point: in about the eight minute of the movie, a slick hockey apparel salesman makes a blunt pitch about wanting to cash in on the team’s emotional resonance with fans and their coach’s national profile. The message to children like me was clear: sponsorship equals success.

–How was I blind to that so-unsubtle-it’s-insane product placement in “Aspen Extreme”? Check out the scenes when they’re “sharpening” their skis. The K2 logos could not have been more obvious if they’d been tattooed on T.J.’s face. Then there’s the constant Coors beer, a major plot point involving Powder Magazine, and even a quick tangent involving ESPN. And did I mention that the movie carries in its title the name of a major American ski corporation?

(Makes you wonder if a little more money had changed hands maybe we’d have had “Telluride Extreme”? Or “Squaw Valley Extreme”? Or what about “Hunter Mountain Extreme”? What would “Hunter Mountain Extreme” have looked like? Maybe T.J. falls asleep on the drive west, and with Dexter in charge of the map, instead of Colorado, the pair wind up in the Catskills? Maybe instead of Bryce Kellogg, T.J. shacks up with a gum-chewing Marla Maples lookalike from Hoboken? Instead of nourishing his writing career, maybe she’s forcing him to watch her two kids while she’s working at the nail parlor? I guarantee you Dexter would have fit in a lot better in “Hunter Mountain Extreme” than he ever did in Aspen.)

–Then there is the most appalling product placement in any children’s film ever. “Home Alone II: Lost in New York” — one of my childhood staples — is now almost impossible for me to rewatch because in retrospect it was basically one giant plug for a Donald Trump-owned property (the Plaza Hotel, owned quite disastrously at the time by our future Troll-in-Chief — who even had a cameo). I don’t want to talk about this.

***

As you can tell, I’ve been reevaluating basically my entire childhood as a result of this documentary. The saddest part to me is thinking about how easy it is for companies to influence children. They’re defenseless — their favorite snuggle toys and cartoon characters are being used to swipe money from their parents — and they won’t even realize it until they’re 35 years-old and paying their first mortgage payments.

The film describes how in the late 1970s, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) considered banning the practice of explicitly advertising to children eight years or younger. But a combination of food company lobbying efforts and the rolling tide of Reagan-era deregulation not only beat back the regulators, but left the FTC stripped of its power. There’s a brief, telling clip of the winning arguments, made by a lawyer for Kellogg’s. His point: in a democratic society, one of the responsibilities we shoulder in having a free market is the responsibility to make informed choices. Surely a sensible description of capitalism, but how — I wondered — do free-market backers expect children younger than eight to be informed consumers? They’re not capable of weighing the evidence; they’re still working on things like “fine motor skills” and “not wetting the bed.” Come on, Ronald Reagan.

My students like to argue that it’s parents’ jobs to ward off the children’s cravings. “I’d be a better, more firm parent,” they seem to say, but one look at the expensive, brand-name phone distracting them from focusing in school, and the gaudy brand logos that adorn every piece of clothing they own speaks otherwise. I suppose it is parents’ responsibility to cart their kids out of WalMart toyless even if they start kicking and screaming. But it seems to me that they’re losing that fight more than winning it. Hardly surprising when they’re up against the ad industry’s brain trust. $1.2 trillion is a big number.

And that last piece of this that seems so sad to me is the simple fact that advertisements today aren’t just selling products, they’re selling values. Deep down, kids’ ads seem to be saying two things: “Wanting stuff is important” and “You are what you own.” Where once children’s ads simply showed a cool product, now they show cool kids using a product — with the implication being that if you don’t buy the product, you aren’t cool.

While all of this has been pretty jarring to think about, it’s been a pleasure to explore these themes through a great documentary alongside intelligent and curious 11th and 12th grade students. Still, the whole experience is enough to make you want to raise a kid without the media at all — no TV, no phone, no Internet. Sounds impossible, but maybe that way he’d be spared all the endless marketing, the branding of everything, the commercialization of childhood?

Now about that cabin for sale in the woods . . . ?